Now that Centene Corporation has announced that they will build their new 750,000 S.F. headquarters Downtown at Ballpark Village, what will become of Forsyth & Hanley? Opened on September 21st, 1951, The building known most recently as Library Limited (the bookstore I miss terribly) by Harris Armstrong was built as the first suburban branch of Scruggs Vandervoort Barney Department Store. Photo above from the Mercantile Library Collection.

Now that Centene Corporation has announced that they will build their new 750,000 S.F. headquarters Downtown at Ballpark Village, what will become of Forsyth & Hanley? Opened on September 21st, 1951, The building known most recently as Library Limited (the bookstore I miss terribly) by Harris Armstrong was built as the first suburban branch of Scruggs Vandervoort Barney Department Store. Photo above from the Mercantile Library Collection.

"Since the automobile has become such a powerful source toward decentralization throughout the country, we feel that the beginning of Vandervoort's suburban store, as part of our modernization and expansion program, is a particularly appropriate feature of our centennial year, which begins a new century for us." These were the words of Frank M. Mayfield, president of Scruggs Vandervoort Barney, Inc. about their new store in Clayton.

"Since the automobile has become such a powerful source toward decentralization throughout the country, we feel that the beginning of Vandervoort's suburban store, as part of our modernization and expansion program, is a particularly appropriate feature of our centennial year, which begins a new century for us." These were the words of Frank M. Mayfield, president of Scruggs Vandervoort Barney, Inc. about their new store in Clayton.

Ironically sales at the Clayton branch were so strong that it sucked the life out of their Downtown store that was housed in the Century and Syndicate Trust Buildings. The resulting losses eventually led to the closure of both the Downtown and Clayton stores in 1967.

Before the announcement Sunday of Centene's move Downtown, this sign foretold the buildings doom. Just over 56 years from the day of its opening, the building that was built out of the idea of moving to the suburbs may have been saved (for the moment) by a reversal of the very trend from which it was built.

Before the announcement Sunday of Centene's move Downtown, this sign foretold the buildings doom. Just over 56 years from the day of its opening, the building that was built out of the idea of moving to the suburbs may have been saved (for the moment) by a reversal of the very trend from which it was built. Reduced to "Bldg. B". The original canopy extending out to Forsyth was removed years ago by a former owner. Architecturally though, most of the building's features are intact, including the cantilevered sun screen below and the tightly strung awnings that stretch from the parking garage to the rear entrance doors.

Reduced to "Bldg. B". The original canopy extending out to Forsyth was removed years ago by a former owner. Architecturally though, most of the building's features are intact, including the cantilevered sun screen below and the tightly strung awnings that stretch from the parking garage to the rear entrance doors. The only problem is that Centene overpaid for the building to the tune of $12 million on the assumption that this cost would be absorbed into the total development cost of the site. Now either Centene has to take a loss on the building, or someone will pay that much for the site with the same thought that the cost will be justified by the redevelopment of the site. Time will tell if someone has the creativity to develop something on the parking garage portion of the site and preserve Harris Armstrong's Forsyth legacy. With Mehlman's proposed development just east, the building (and Forsyth in between) could be poised once again to become a great retail destination.

The only problem is that Centene overpaid for the building to the tune of $12 million on the assumption that this cost would be absorbed into the total development cost of the site. Now either Centene has to take a loss on the building, or someone will pay that much for the site with the same thought that the cost will be justified by the redevelopment of the site. Time will tell if someone has the creativity to develop something on the parking garage portion of the site and preserve Harris Armstrong's Forsyth legacy. With Mehlman's proposed development just east, the building (and Forsyth in between) could be poised once again to become a great retail destination.

"Today, Mercantile does not have an appropriate entrance to our corporate headquarters". This was the sorry excuse that Ralph Babb, vice-chairman of Mercantile Bank gave at a Heritage and Urban Design Commission hearing in January 1995 to demolish the Ambassador Theater along with a dose of the standard "its too far gone" bullshit. Succumbing to pressure from the "whatever the businesses want" mindset of SLDC director Larry Bushong, the HUDC rolled over and granted the demolition permit.

"Today, Mercantile does not have an appropriate entrance to our corporate headquarters". This was the sorry excuse that Ralph Babb, vice-chairman of Mercantile Bank gave at a Heritage and Urban Design Commission hearing in January 1995 to demolish the Ambassador Theater along with a dose of the standard "its too far gone" bullshit. Succumbing to pressure from the "whatever the businesses want" mindset of SLDC director Larry Bushong, the HUDC rolled over and granted the demolition permit.

No "appropriate entrance"!!?? I guess it was not enough that for almost 20 years since its completion in 1976 that the Mercantile Tower had done very well with the landscaped plaza on Washington Avenue complete with its iconic chrome sculpture: Synergism by artists William Severson and Saunders Schultz. Apparently bank officials didn't think this was enough and insisted upon importing a slice of Maryville Office Center into Downtown St. Louis.

The photo above from PPS shows the tower's entrance plaza on Washington Avenue. Also at right is the columned facade of the Loews State Theater and two other narrow buildings that were demolished in the early 90's to make way the expansion of the convention center (the auditorium of Loews had been demolished almost a decade earlier in 1983).

The photo above from PPS shows the tower's entrance plaza on Washington Avenue. Also at right is the columned facade of the Loews State Theater and two other narrow buildings that were demolished in the early 90's to make way the expansion of the convention center (the auditorium of Loews had been demolished almost a decade earlier in 1983).

The Ambassador rose 17 stories with eleven office floors above the theater at 7th and Locust Streets. It was completed in 1926 by architects C.W. and George L. Rapp of Chicago. Its opening was promoted as the greatest event in St. Louis since the World's Fair (I wonder how many times that claim was used). In the photo above of the Locust Street facade, above the terra cotta was a row of blank window openings. These concealed the massive trusses that supported the office floors above. More on those below.

The Ambassador rose 17 stories with eleven office floors above the theater at 7th and Locust Streets. It was completed in 1926 by architects C.W. and George L. Rapp of Chicago. Its opening was promoted as the greatest event in St. Louis since the World's Fair (I wonder how many times that claim was used). In the photo above of the Locust Street facade, above the terra cotta was a row of blank window openings. These concealed the massive trusses that supported the office floors above. More on those below. With the context of the three story bank building to the west, the architects chose to wrap the decorative cornice across the entire west elevation of the wing. Typically a cornice would only be wrapped around the corner from the street one bay or less.

With the context of the three story bank building to the west, the architects chose to wrap the decorative cornice across the entire west elevation of the wing. Typically a cornice would only be wrapped around the corner from the street one bay or less. Looking up at the 7th street facade near the corner at Locust

Looking up at the 7th street facade near the corner at Locust Terra cotta detailing above the theater entrance

Terra cotta detailing above the theater entrance

Facade of the theater lobby along Locust Street

Facade of the theater lobby along Locust Street Close-up of the terra cotta along Locust

Close-up of the terra cotta along Locust The beautiful bronze plaque next to the office entrance on 7th street. The Skouras Brothers financed the construction of the building.

The beautiful bronze plaque next to the office entrance on 7th street. The Skouras Brothers financed the construction of the building. Griffins, Venetian blinds, and a flag pole along 7th Street

Griffins, Venetian blinds, and a flag pole along 7th Street Demolition of the lower floors along 7th Street

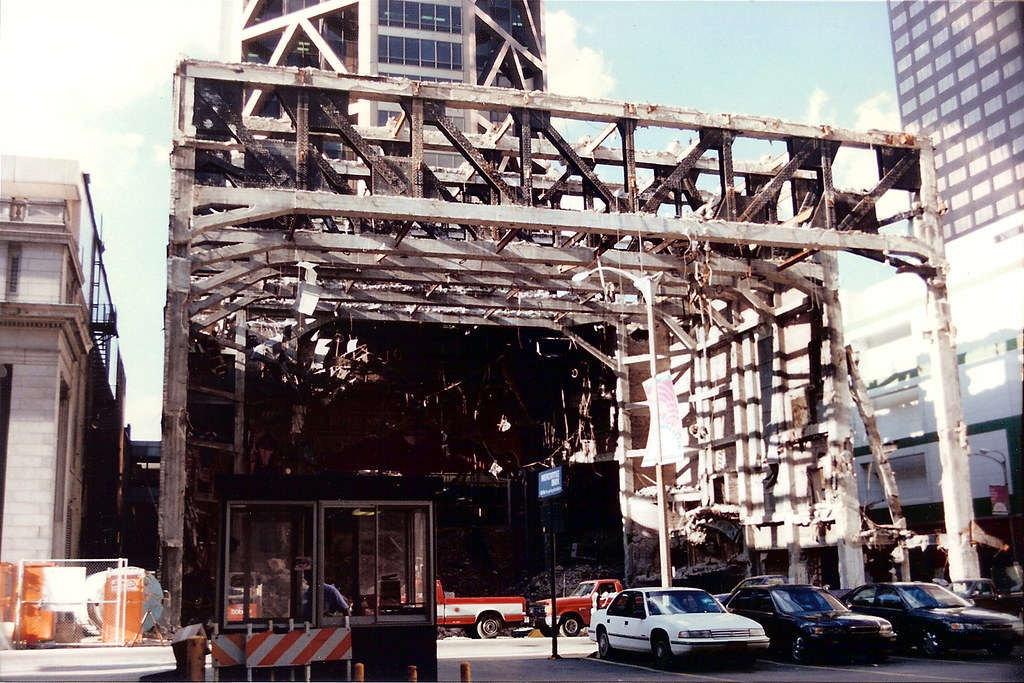

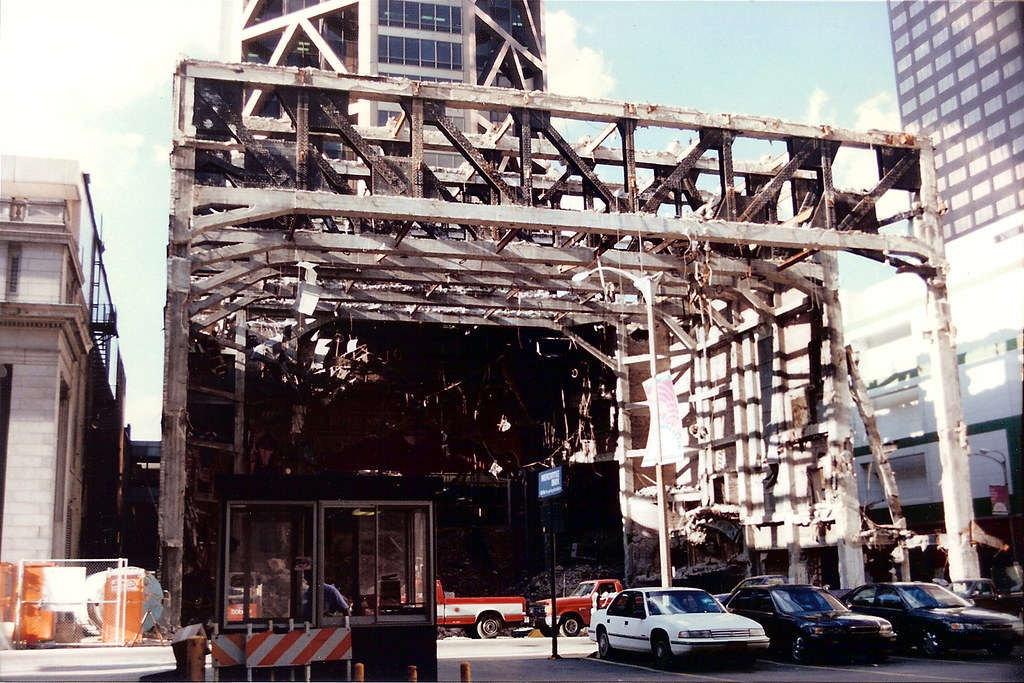

Demolition of the lower floors along 7th Street After demolition of the remainder of the building, all that remained was the super-structure including the giant concrete filled trusses, which were apparently a surprise to Spirtas, the demolition contractor.

After demolition of the remainder of the building, all that remained was the super-structure including the giant concrete filled trusses, which were apparently a surprise to Spirtas, the demolition contractor. The headache ball was unable to make the trusses budge. The building had its last revenge, and a large crane and scaffolding had to be brought in to remove the trusses in pieces.

The headache ball was unable to make the trusses budge. The building had its last revenge, and a large crane and scaffolding had to be brought in to remove the trusses in pieces. The last curtain call

The last curtain call Seen from the stairwell of the Chemical Building is the glorified driveway that Mercantile installed as their "appropriate entrance".

Seen from the stairwell of the Chemical Building is the glorified driveway that Mercantile installed as their "appropriate entrance". In a token attempt at pleasing anyone with memories of the theater, offices or an appreciation for historic architecture, some terra cotta panels were installed on the back-side of the original bank building. To bad they couldn't even bother to cover up the lovely mechanical shed on the roof.

In a token attempt at pleasing anyone with memories of the theater, offices or an appreciation for historic architecture, some terra cotta panels were installed on the back-side of the original bank building. To bad they couldn't even bother to cover up the lovely mechanical shed on the roof.

For more photos of the demolition and several by Toby Weiss of the beautiful interior prior to being stripped, take a look at these pages on Built St. Louis.

Now that Centene Corporation has announced that they will build their new 750,000 S.F. headquarters Downtown at Ballpark Village, what will become of Forsyth & Hanley? Opened on September 21st, 1951, The building known most recently as Library Limited (the bookstore I miss terribly) by Harris Armstrong was built as the first suburban branch of Scruggs Vandervoort Barney Department Store. Photo above from the Mercantile Library Collection.

Now that Centene Corporation has announced that they will build their new 750,000 S.F. headquarters Downtown at Ballpark Village, what will become of Forsyth & Hanley? Opened on September 21st, 1951, The building known most recently as Library Limited (the bookstore I miss terribly) by Harris Armstrong was built as the first suburban branch of Scruggs Vandervoort Barney Department Store. Photo above from the Mercantile Library Collection. "Since the automobile has become such a powerful source toward decentralization throughout the country, we feel that the beginning of Vandervoort's suburban store, as part of our modernization and expansion program, is a particularly appropriate feature of our centennial year, which begins a new century for us." These were the words of Frank M. Mayfield, president of Scruggs Vandervoort Barney, Inc. about their new store in Clayton.

"Since the automobile has become such a powerful source toward decentralization throughout the country, we feel that the beginning of Vandervoort's suburban store, as part of our modernization and expansion program, is a particularly appropriate feature of our centennial year, which begins a new century for us." These were the words of Frank M. Mayfield, president of Scruggs Vandervoort Barney, Inc. about their new store in Clayton. Before the announcement Sunday of Centene's move Downtown, this sign foretold the buildings doom. Just over 56 years from the day of its opening, the building that was built out of the idea of moving to the suburbs may have been saved (for the moment) by a reversal of the very trend from which it was built.

Before the announcement Sunday of Centene's move Downtown, this sign foretold the buildings doom. Just over 56 years from the day of its opening, the building that was built out of the idea of moving to the suburbs may have been saved (for the moment) by a reversal of the very trend from which it was built. Reduced to "Bldg. B". The original canopy extending out to Forsyth was removed years ago by a former owner. Architecturally though, most of the building's features are intact, including the cantilevered sun screen below and the tightly strung awnings that stretch from the parking garage to the rear entrance doors.

Reduced to "Bldg. B". The original canopy extending out to Forsyth was removed years ago by a former owner. Architecturally though, most of the building's features are intact, including the cantilevered sun screen below and the tightly strung awnings that stretch from the parking garage to the rear entrance doors. The only problem is that Centene overpaid for the building to the tune of $12 million on the assumption that this cost would be absorbed into the total development cost of the site. Now either Centene has to take a loss on the building, or someone will pay that much for the site with the same thought that the cost will be justified by the redevelopment of the site. Time will tell if someone has the creativity to develop something on the parking garage portion of the site and preserve Harris Armstrong's Forsyth legacy. With Mehlman's proposed development just east, the building (and Forsyth in between) could be poised once again to become a great retail destination.

The only problem is that Centene overpaid for the building to the tune of $12 million on the assumption that this cost would be absorbed into the total development cost of the site. Now either Centene has to take a loss on the building, or someone will pay that much for the site with the same thought that the cost will be justified by the redevelopment of the site. Time will tell if someone has the creativity to develop something on the parking garage portion of the site and preserve Harris Armstrong's Forsyth legacy. With Mehlman's proposed development just east, the building (and Forsyth in between) could be poised once again to become a great retail destination.